They should have let Amanda Knox talk more. When she’s sitting there on screen, going through the details of what happened to her and describing the ordeal she went through, the latest true crime documentary that everyone will have an opinion about is insightful and engaging. The film is unabashedly Pro-Knox—-and really, how could it not be? She wouldn’t sit there for hours going over the worst period of her life for a film convinced of her guilt—-and when it simply stands back and lets her talk, it’s an effective piece of documentary filmmaking. Alas, most of the film is focused on painting the Italian prosecutors and members of the news media as diabolical, amoral villains while wasting time in a vain attempt to doll out suspense in service of developments most people are already aware of. It wants to stand above the type of sensationalistic journalism that led to Knox’s conviction and incarceration but refuses to acknowledge or even comment on the fact that it could not exist without those lurid news stories in the first place.

Ever since HBO’s The Jinx captured everyone’s attention, our desire for new true crime documentaries seems to have become insatiable. Netflix’s Making a Murderer is getting a second season and there’s an HBO doc about Slender-Man hitting TV screens in 2017. We got a Scientology doc last year and there’s another one on the way. Ava DuVernay’s 13th is currently playing to rave reviews at the New York Film festival and let’s not forget how we all got transported back to 1992 a few months ago when O.J. Simpson was the subject of a TV mini-series and an extended docu-series. There’s even a CBS special about Jon Benet Ramsey airing right now. I was as captivated by The Jinx as everyone else but when it concluded, I had a disturbing thought. I said to myself, “Man, I can’t wait for the next one of these!” And then I thought about the implications of what had gone through my head. Was I really hoping for more terrible things to happen in the world so I could sit back and watch them all unfold from a removed place of judgment? Yeah, I suppose I was. And while that’s somewhat natural (at least I hope it is) and indicative of a society that gobbles up lurid true crime stories like they’re candy, it’s also somewhat sick and pretentious.

Let’s focus on that last part. While watching Amanda Knox, I wondered how different I was than the millions of people who watched her story unfold on the news or in the tabloids. The film condemns the news media time and time again for publishing stories with cheesy headlines like “Foxy Knoxy’s Sexy Orgy” and consistently points the finger at people like Nick Pisa, a British journalist who spends as much time talking to the camera as Knox does. Pisa freely admits his biggest concern was getting a story to the printers before his competitors did. He even published Knox’s diary and when the filmmakers ask him how he obtained it, he bristles and says that revealing his sources would violate his “journalistic principles”. Later in the film, he cheerfully admits he didn’t fact check anything given to him because he didn’t have time. It’s quite simple then isn’t it? Pisa and others like him are monsters; bottom feeders looking for the quickest way to gloriously lurid headlines, right? Wrong. Pisa and others like him are easy targets. Straw men that the movie can swiftly knock down and condemn. The film is so goddamn tone deaf that it doesn’t even pick up on the fact that Pisa is fully aware of how he’s being portrayed and clearly doesn’t give a shit. To him, that’s how the game was played. How are we, the viewers of this film, any different in our indignation towards Pisa than the people who followed Knox’s sordid tale and judged her guilty based on trumped-up news stories?

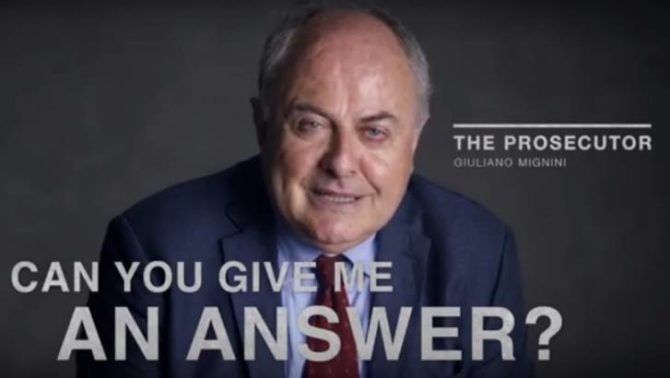

To be fair, Pisa is slime. No doubt about that. But isn’t he part of a larger problem? It’s a cheap trick to have the only journalist in your documentary be a smug British guy. There’s hardly anyone easier to hate than a smug British guy. Except maybe a smug Italian guy. Don’t worry though, cuz Amanda Knox has one of those too. His name is Giuliano Mignini and he was the lead prosecutor against Knox. Right away, he’s presented as an ego-maniac, comparing himself to Sherlock Holmes and going on about divine judgement. Two things come to mind: (1.) Show me a tough as nails prosecutor who has not compared himself to Sherlock Holmes at some point in his career and I’ll show you a liar. (2.) It seems spectacularly unfair and small-minded to criticize a man for having faith and for applying said faith to his work. Mignini states that he believes God gave man free will and as a result, all men must be held accountable for their actions. That’s a decent belief for a prosecutor to have, in my not-so humble opinion. But is the film interested in looking at Mignini as a well-intentioned man who got swept up by a media circus and a desire for answers so overwhelming that it was all he could do to not blame the man standing next to him for the death of Meredith Kercher? Of course not. In the filmmaker’s eyes, Mignini is a dangerous zealot and a gloriously incompetent public servant. There’s no room for nuance, no look at the outside forces around him, and no room for mistakes. To be fair once again though, I have no love for religion and think Mignini is a giant asshole who came to a conclusion way too early and refused to consider any other possibility. But pointing the finger directly at him and ignoring all the other outside forces is a way for the filmmakers to take the easy way out. It allows us to look down on these people who condemned Amanda and say, “I would never have done such a thing” without considering any of the external or internal forces that caused them to do so.

Another problem is the severe lack of Meredith Kercher in the film. Yes, the documentary is called Amanda Knox but Kercher was the victim she was accused of murdering. You would think the film would have a little more to say about her than the tabloids did but it doesn’t. Her family is largely absent from the narrative—-which is expected, I’m sure they have no desire to participate in interviews—-and when they are present, they’re portrayed as dummies who accepted the story that was gift wrapped to them by prosecutors and the media. No thought at all is given to why they would want to believe the people who killed their daughter had been caught and there’s hardly any sympathy for their plight. Kercher’s mother pops up in archival footage towards the end of the film and this feels both too little too late and somewhat distasteful. She’s there so the filmmakers can double down on Knox’s innocence, as if to say, “See? Even the mother of the victim has doubts!” By this point, we’re more than convinced of Amanda’s innocence and don’t need to see a grieving woman struggling to make sense of what happened to her daughter. All the news stories surrounding the case were focused on Amanda, not Meredith. How is the documentary any better by taking the exact same approach as the news stories it has such disdain for?

A great documentary is a hard thing to make but films like Amanda Knox and shows like Making a Murderer seem to fail to understand what a documentary even is supposed to be. And that shouldn’t be so hard. It’s right there in the name. A documentary should be a document of a time period or an event. It’s a despicable misconception that a documentary is supposed to be objective. It should always have a point of view. But when that point of view is presented in lieu of the real issues under the surface, then you have a serious problem. The three best documentaries I’ve ever seen are Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky’s Paradise Lost series, Tony Kaye’s Lake of Fire, and Ezra Edelman’s O.J.: Made In America. All three had a distinct point of view and backed up that point of view with evidence and convincing testimony. All three were also unafraid to look at their subjects from every possible angle. In the Paradise Lost series, a man deemed a murderer is gradually revealed to be nothing more than a sad, flawed human being in desperate need of answers. In Lake of Fire, people on all sides of the abortion debate are shown to be capable of great acts of cruelty. In O.J.: Made in America, every single aspect of a man’s life, upbringing, environment, and temperament is examined against a back drop of racial injustice and society’s desire for a good story.

Amanda Knox has no interest in exploring anything remotely complicated. It’s a story of a falsely accused girl who was exonerated. That’s it. Don’t get me wrong, I’m glad Knox is free and believe what happened to her to be a terrifying miscarriage of justice indicative of a society sick at its core. But the documentary about her only pays lip service to such an idea. Rather than explore the way journalism works and how much pressure investigators are under to solve a crime, it instead chooses to paint its story in broad strokes by giving us a noble hero and vile villains. As we all know, real life is never so simple as that. The film left me in a state of depression and rage. Not because of the subject matter but because I felt I was mourning the loss of an art form. If Amanda Knox, like the reprehensible Making a Murderer, is a hit then we are only going to get more and more documentaries that ignore facts and larger societal themes in service of simple stories with easy endings. In other words, it’ll soon be hard to tell the difference between a documentary and an issue of People magazine.

GET CHOMPED