High-Rise Is An Overcooked Yet Enthralling Take On J.G. Ballard’s Classic Book

“It’s a human zoo

A suicide machine!”– High Rise by Hawkwind, sadly not featured in this film.

Published in 1975, J.G. Ballard’s grim, dystopian vision is far removed from today’s artistic climate where calls for trigger warnings and safe spaces reverberate across the pop culture landscape with ever greater frequency. That a film of High-Rise has been released in 2016 is a lustrous beacon of hope, even if the long-waited end result is a mixed bag.

Dispassionate anthropologist Robert Laing (Tom Hiddleston) moves into the 25th floor of a luxury tower-block recently brought to life by eccentric architect Anthony Royal (Jeremy Irons). Royal’s building is a magnum opus, providing its tenants with an abundance of amenities such as a swimming pool, a supermarket, and even a school. Laing quickly acclimates to his comfortable new life in the high-rise. After all, what could possibly go wrong in a society where instant access is valued above everything else?

A man mysteriously falls from the 39th floor to his death, but the matter is never investigated. The parking lot becomes a graveyard of mangled luxury cars. The middle-class residents on the lower levels experience power failures while the upper-class residents occupying the higher levels can siphon all the electricity they’d like for their pretentious, debauched parties. A class war erupts. The lower-level tenants find a leader in Richard Wilder (Luke Evans), an unbalanced barbarian who rouses the outraged hordes into pillaging the higher floors.

Laing floats above the chaos, watching the carnage play out with a neutral gaze while occasionally allowing members on both sides of the conflict to physically or sexually exploit him. The high-rise, a character in its own right, assimilates Laing into its painstaking geometric architecture. “You are definitely the most amenity in the building,” says one tenant of Laing. “He knows his place,” says another.

The challenge in adapting High-Rise was in capturing its quietly unnerving tone. Ballard’s novel, regarded by some as an essential counter-culture text, begins at a point of acute anxiety and unravels from there. It’s a surreal book but one that always feels grounded in plausibility. As the narrative leapfrogs between its three central characters — Laing, Royal, and Wilder — the reader develops a deeper understanding of the building’s inner workings. Ballard’s prose reads like a published scientific journal recounting a sociological experiment gone horribly awry. The high-rise represents unrestricted consumer culture at its most amoral, its collapse inevitable due to a faulty foundation on “unlimited possibilities.” It’s a disdainful satire on class warfare as well as the media’s role in perpetuating it: Wilder, a TV producer, feels the need to record his psychotic brand of vigilante justice for the purposes of a documentary. Imagine that: someone with a background in television wreaking havoc on society for his own egotistical motives while his myriad savage supporters carry out his hateful dirty work. Why does that ring such a robust bell today?

The novel is a slow burn, not unlike Ben Wheatley’s previous films Kill List and A Field in England. The power of Wheatley’s filmmaking comes from his facility for plunging into the broiling rage lurking beneath the mundane surface of the British middle class. Wheatley seemed like the perfect filmmaker to realize Ballard’s ruthless, clinical vision of corpulent capitalism at its ugliest.

So it’s strange that Wheatley and screenwriter Amy Jump have opted for such an aggressively visceral approach. The plot is faithfully adhered to, but there is a stark contrast in tone. This contrast is obvious within the first few seconds of the film. Consider the novel’s opening line: “Later, as he sat on his balcony eating the dog, Dr Robert Laing reflected on the unusual events that had taken place within this huge apartment building during the previous three months.”

Now the thought of eating a dog alone is enough to churn the stomachs of the popcorn-chomping masses. But it’s the lack of a definable tone, that deadpan nature of the prose, that makes the imagery so disturbing. There is never an attempt to comfort the reader. It’s one of the reasons that High-Rise was considered “unfilmable” for so many years.

But in its execution of that unforgettable first line, High-Rise eschews this distance. The camera swoops in and around Laing’s flat as we watch him cook the dog. A delightful Bach concerto plays over this nihilistic scene. Moments later, we cut to the wreckage of the tower block rebellion: corpse heaps, flooded corridors, and a benign but homicidal dentist of the Michael Palin in Monty Python variety (here played by the excellent Reece Shearsmith). The tonality is more obviously comedic. While this serves to make the story more palatable for a wider audience, its effects on the narrative are spotty. The book may be a slow burn, but High-Rise the movie douses itself in gasoline and lights a match in the first five minutes.

The problem is that an extreme allegory like the one offered up in High-Rise requires a scalpel, not a sledgehammer. Wheatley picked up the sledgehammer. High-Rise starts at a level of feverish insanity and has nowhere to go. Jump’s screenplay makes an admirable attempt to flesh out the supporting characters, but her solution is to stuff the script with comic dialogue that intermittently amuses but offers little insight into the characters who are speaking it. As a result, High-Rise sometimes feels like a series of disjointed thumbnail sketches interspersed with moments of standard Ben Wheatley slow-motion tableaux. While such moments were downright chilling in A Field in England, here they play out like aimless and overproduced music videos from a growling, three-chord punk band who sounded a lot better using lo-fi technology–Portishead’s much-publicized cover of ABBA’s S.O.S. plays out over the worst of said sequences.

High-Rise may be an uneven film but there is still plenty to recommend. Ballard’s thesis may be watered-down but it does exist, and it still resonates today. We increasingly value convenience and instant access above all else; trust in establishment figures is at an all-time low; many of us are still reeling from the effects of the global financial crisis; and the confused, angry masses have turned to salvation in the form of a garish loudmouth with a shit haircut. The same problems that befell us in the 1970s still dog us today, and it’s exhilarating to see those problems explored in such an ambitious and angry film. I’ve seen High-Rise compared to the works of Stanley Kubrick and Nicolas Roeg, but I was most often reminded of Alex Cox in his prime: unsubtle, playful, and ever-so-nasty.

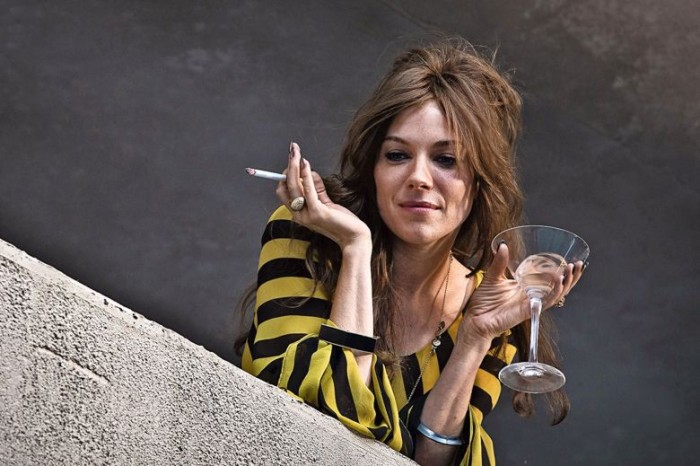

Clint Mansell’s score is a rich blend of sweeping classical motifs and folk-inflected horror cues reminiscent of British horror touchstones The Wicker Man and Witchfinder General. The performances are committed and eclectic, but Luke Evans is the true revelation. His vigorous, masculine presence has been compared aptly to that of the great Oliver Reed. The joy of watching Tom Hiddleston as the inscrutable Laing is in witnessing his startling vulnerability whenever he gives into his id and releases the beast within. Sienna Miller impresses despite her underwritten role. Jeremy Irons, however, appears to be doing an impression of Jeremy Irons doing an impression of Jeremy Irons doing an impression of Jeremy Irons in The Lion King–you can decide whether or not that’s a good thing.

High-Rise is not for everyone. Despite my reservations, I was enthralled by the film and I suspect I’ll like it more after subsequent viewings. Ben Wheatley remains one of the most exciting new filmmakers working today, and even a messy Ben Wheatley film is more worthwhile than most of the crap coming out of Hollywood. Fans of the Ballard text would do well to alter their expectations accordingly. No, it’s not as good as the novel, but it was never going to be. Still, High-Rise is worth seeing for its sheer audacity: a bold and entrancing paranoid thriller that reflects the times we live in by holding up a kaleidoscopic mirror to the past–although I really could’ve done without that awful Mrs. Thatcher joke at the very end.

And finally, because this is a web site for nerds, I leave you with Loki in his birthday suit.

GET CHOMPED